We're deep in the holiday season a time filled with nostalgia and for this month's book club author Jen Campbell has decided to look back at her favourite childhood reads. Revisiting favourites can sometimes be a dispiriting thing the characters not quite as we remembered, the plot lacking the magic it once had. Not so with the book Jen has chosen

Having read and loved Carrie's War at the age of nine, I raided my school library for other books set during the Second World War. It was there that I found a book whose battered cover showed a family at a train station surrounded by suitcases. It was heavily dogeared, the pages tanned. The back read:

It was a small piece of red enamel with a black hooked cross on it.

It's called a swastika, said Gunther, all the Nazis have them.'

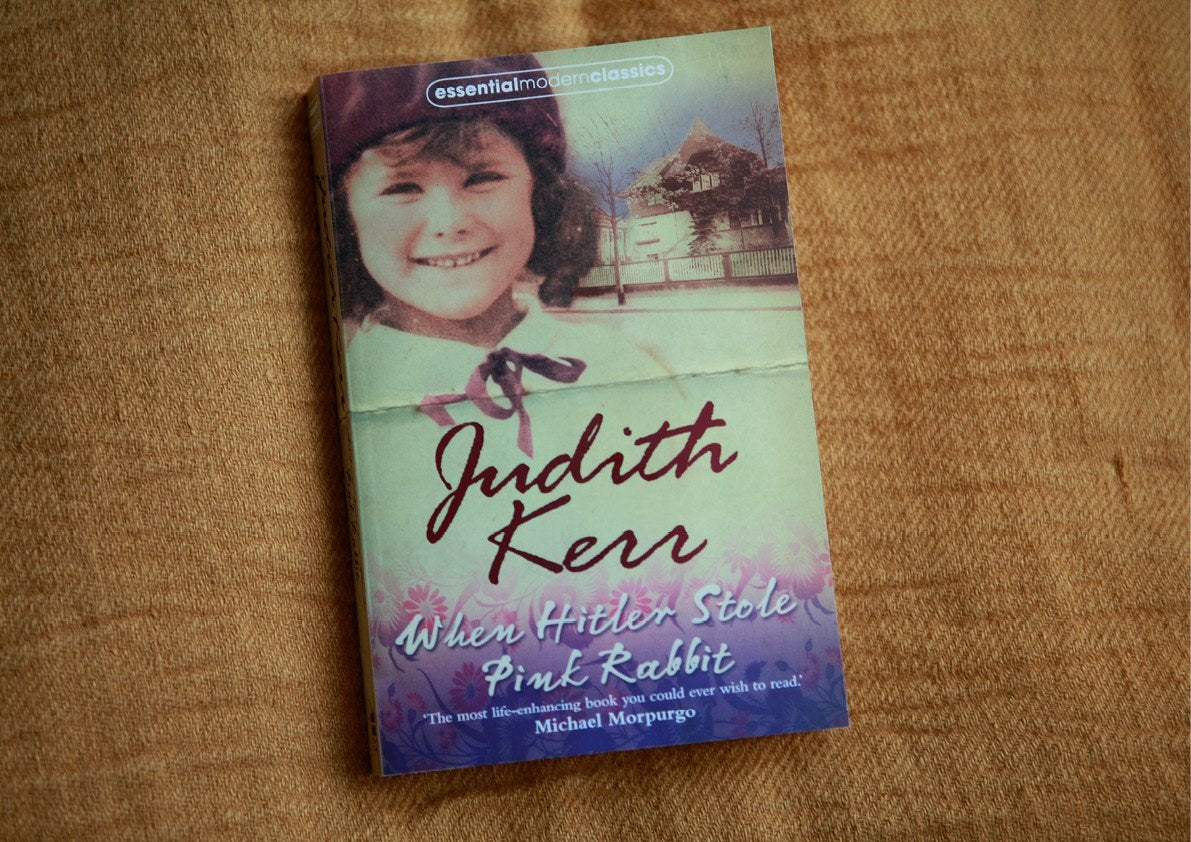

The book was When Hitler Stole Pink Rabbit by Judith Kerr.

Judith Kerr is the author of Mog and The Tiger Who Came to Tea. When Hitler Stole Pink Rabbit is a retelling of her own childhood experiences. Like its protagonist, Anna, her father was a German-Jewish theatre critic and essayist, outspoken against Hitler and, like Anna, Judith and her family fled Berlin a few days before Hitler was appointed chancellor in 1933.

I've lost count of how many times I've read this book normally in bed, as I'm a firm librocubicularist. It's one of those stories that doesn't lose its charm as you grow up; it simply grows up with you. As a child I also sought it out on audio cassette, read by Rosemary Leach, and would fall asleep (or, more often than not, remain wide awake) listening to the captivating story of Anna and her family, fleeing Germany and making their way across Europe to escape the Nazis.

Picture the scene: Anna is nine. She likes to write poems and illustrate them, normally poems about death and disaster, which her teacher bemoans, claiming she should write about flowers and springtime instead. Anna's Papa [gives] a little sideways smile, and [says] perhaps [Anna is] in touch with the times.'

The political situation in Germany is a cloud to Anna and her brother Max. They can see it hovering but they have no idea how terrifying the storm will be. They are told by their parents that they must leave the country, and should not tell anyone they are going. But, instead of being scared, their worries lie in what games and toys they'll be able to take with them.

It's only once they arrive in Switzerland and learn that the day after the election the Nazis came to collect their passports and take all their possessions, that the gravity of the situation hits them. Anna imagines Hitler carrying her pink toy rabbit with him wherever he goes and, for a few chapters, it feels as though Hitler had stolen Anna's childhood.

Whilst I shared Anna's concerns on my first read, it's the subtle, weighted things that stand out to me this time: Anna's father writing in the night, lit by a single lamp an island in the dark; Anna's friend Elsbeth saying her sister thought Hitler was Charlie Chaplin, not realising how different the two of them are; their Swiss teacher claiming cavemen used safety pins to fasten their furs together amusing at first, yes, but ultimately serving to highlight how important it is to get history right.

A few months later, far away from the Hitler they have left behind, Anna (and the childhood reader) is lured into a false sense of security. Everything seems funny, including their grandmother's horrible dog, Pumpel.

Pumpel is an aggressive dachshund who bites everyone in sight, thinks lightbulbs are tennis balls, and seems to have ridiculously reckless tendencies. When Pumpel eventually succeeds in throwing himself into the local lake, and drowns, they bury him in the back garden. Anna's friend throws a chrysanthemum on top of his grave, declaring, smugly: 'Now your doggie can't get out!

It is at this point that Anna overhears Omama telling her mother about a famous professor who was dragged away to a concentration camp. He was tied to a kennel and told to bark for food. He wasn't allowed to eat it with his hands, and after two months of living like this, the famous professor lost his mind. Anna finds it difficult to breathe. So do we. The story of Pumpel, mad and jumping to his death, takes on a whole new meaning: And now your doggie can't get out!'

Following Anna's family as they move from Switzerland to France and finally to England, learning new languages, making new friends, battling with their new identity as refugees, is a story I don't think you could revisit too many times. Perhaps because, sadly, the subject of refugees is something that constantly holds relevance, or perhaps simply because Anna's cravings were universal. Anna, and Judith Kerr, wanted to belong. They wanted a home, surrounded by those they loved. Not only did they make many homes when they were young, travelling from country to country, now they've found homes on bookshelves all around the world.

This review was written by the author and poet Jen Campbell. The book club exists in a purely digital sphere but we hope that you will add your own thoughts and comments below. As a thank you, all those who comment will be entered into a prize draw to win a copy of Convenience Store Woman by Sayaka Murata, the next book to be reviewed.

Add a comment